Large language models promised much a couple of years ago, but their limitations are holding them back from the creation of that killer app.

Research from as early as the 1860s by Charles S. Peirce, dubbed the ‘American Aristotle’, provides clarity on these limitations with his theory of Semiotics. LLMs treat (or work on) language as only ‘form’. But human language is so much more! His theory connects those more complex components for us, like culture, language, evolution and biology - all necessary for what makes up the uniqueness of human-like interaction.

The model has three components: sign, object and interpretant. This can work nicely in meaning-based natural language understanding (NLU) for emulating human language interaction. The sign is the word (form) that represents a particular object. The interpretant is the definition of that word in context. The object is the thing in the real world.

Now, not everything that happened more than 50 years before computers were created was on the right track, but there is substantial research that is being overlooked, ignored, bypassed in the race for ‘AI’ today. Computer science has proverbially ‘thrown the baby out with the bathwater.’

So what’s missing?

What LLMs lack

LLMs use a word vector representation for the strings of text in a document. That means they are vectors, numbers assigned to the dimensions in the model that can compute similarity or difference between any given vectors. Perhaps ‘eat’ is similar to ‘chew’ in some text, but ‘eat’ is unlike ‘speak’ in another text.

The transformer architecture added by Google in 2018 addressed a limitation of word vectors - enabling the same word form to be assigned a different vector depending on the text surrounding it. So in an LLM, the text found maps to a set of numbers. Those numbers are then manipulated along with previously trained references - effectively predicting the next word to generate. Hence the term generative AI, as it generates text from a prompt.

I introduced Peirce’s semiotics. Let me talk more about what a sign can represent. It can be an icon, index or symbol.

An icon resembles something in the real world. A photograph of your face is an icon of you, for example. Diagrams are also icons. A map usually resembles the world to allow navigation. Icons help us understand directions for this reason, left being a particular side of our body, and right being the other. Front and back work well with left and right to explain where things are in relation to the object. North and south relate to an independent reference point, aligned with our globe.

An index points at something in context. When I say ‘you’ I am referencing to a listener in context. If there is one person in context, that person is referenced with an index.

To understand the index, you need access to the full pragmatics, the context at play at the time you hear it. LLMs don’t include human-like complexities such as pragmatics in their model.

In language, it is very important to know context when something is said - who said it, where they were, what else was happening in the conversation. That’s part of pragmatics.

And lastly, there is a symbol, something that the language assigns by convention to something. We agree that a ‘lion’ is a kind of large cat in which the males have a large mane. It needn’t be ‘lion.’ It could be anything that is allowed in the language’s written and spoken constraints, but conventions need to remain stable to be effective.

Testing Microsoft Copilot with some semiotic icons.

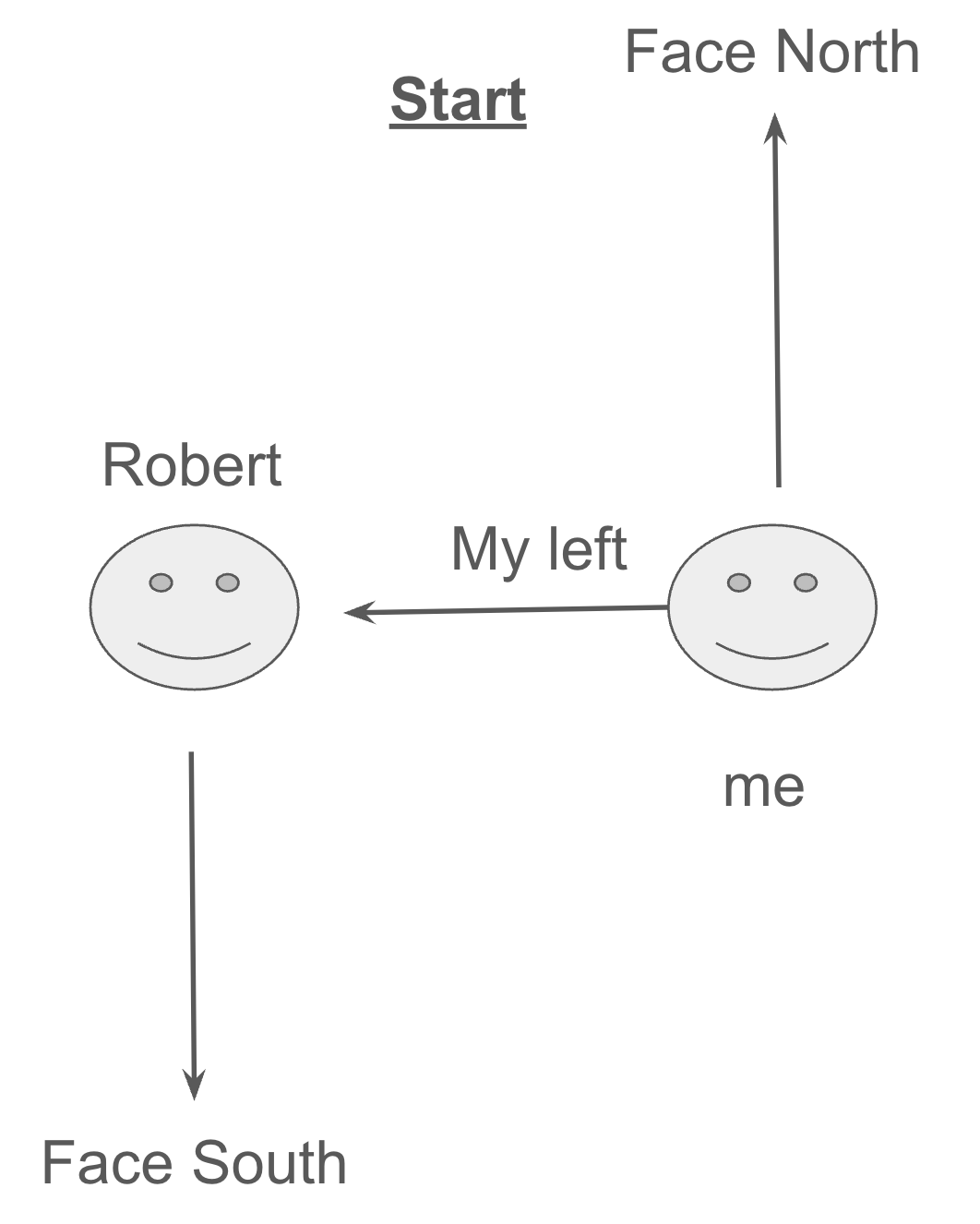

Here are some simple directions that, from memory, could be used in an IQ test. It was impressive the range of MISunderstanding I found in its response!

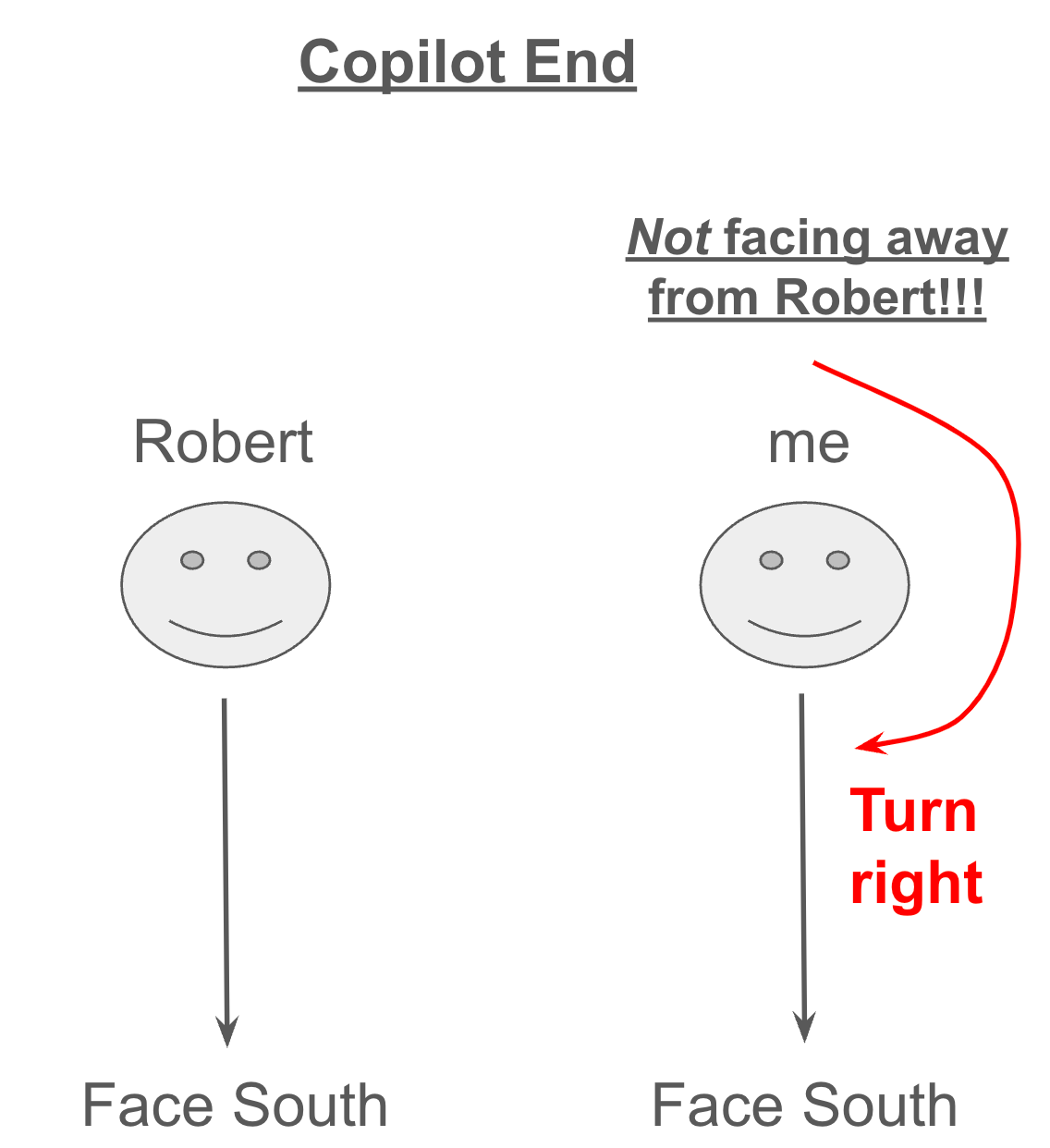

When I say ‘which direction should I turn’ I assume it to be a specific direction, 90°, not a rotation left or right. That’s common sense. The response suggests a rotation to the right of 180° to point south. Common sense says that’s unexpected because you can turn left OR right to make a 180-degree turn.

Aside: In the military, it would be unambiguous - e.g. LEFT FACE, ABOUT FACE, RIGHT FACE, HALF-RIGHT FACE (45°), …

The LLM instruction faces me the same way that Robert is facing, not away from him as requested. But it writes that I am ‘directly opposite’ him. That makes no sense at all!

The correct answers I expected would have been ‘turn east’ or ‘turn right’ (assuming 90°).

This example shows how an LLM isn’t working properly with language that uses an icon, or diagram, for the sign (word) interpretation at least in this one example. That was the first one I tried.

In my own head, this doesn’t feel like a language problem. I need to visualize the direction I’m facing, where Robert is, and how his relation to me determines my movement. But it’s a very basic spatial example. Spatial examples have been well documented back in 2000, such as in the book by Leonard Talmy, Toward a Cognitive Semantics. A lot of the hard work has already been done!

Conclusion

In today’s example, one of the key building blocks identified in the 1800s was tested against Microsoft Copilot. This time, copilot did not generate a response that makes sense at all.

To test how a brain does this we could analyze brain region activation. Is the area that compares me and Robert visual? If so maybe we see activation in the occipital lobe. Or maybe we see something in the parietal lobe, that is involved in the touch sense and multiple senses we can ‘use.’ Maybe both? Maybe neither. This involves the granularity required to interpret what our brain is doing; that’s science. We would know more with experimentation.

I’d bet on the left parietal lobe, as the internet tells me that damage to it can result in ‘right-left confusion’ like copilot. That deficit in humans is what is called "Gerstmann's Syndrome."

So what are LLMs missing that hold them back from creation of that AI killer app? The right models - with meaning and context - that deal with the complexities of human language. That same human language that makes us uniquely ‘intelligent’.

here is what ChatGPT replied to the same prompt:

"To face away from Robert, you should turn to your right.

Here's how it breaks down:

If you're facing North, Robert is to your left and facing South.

To face away from Robert, you need to face the opposite direction of where Robert is looking.

Robert is facing South, so to face away from him, you need to face North or the direction opposite to South.

Since you’re already facing North, turning right (East) will align you with a direction that’s opposite to South."